Charles Jencks is the

author of several books on art and architecture. In 2004 he won

the Gulbenkian Prize for Museums with his design for Landform

Ueda. His most recent book is The Iconic Building .

.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

What is an “iconic building?”

What, in your opinion, are the best examples of the genre?

The

iconic building shares certain aspects both with an iconic object,

such as a Byzantine painting of Jesus, and the philosophical definition

of an icon, that is, a sign with some factor in common with the

thing it represents. On the one hand, to become iconic a building

must provide a new and condensed image, be high in figural  shape or gestalt, and stand out from the

city. On the other hand, to become powerful it must be reminiscent

in some ways of unlikely but important metaphors and be a symbol

fit to be worshipped, a hard task in a secular society.

shape or gestalt, and stand out from the

city. On the other hand, to become powerful it must be reminiscent

in some ways of unlikely but important metaphors and be a symbol

fit to be worshipped, a hard task in a secular society.

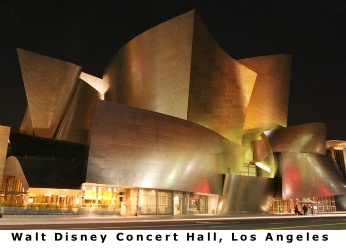

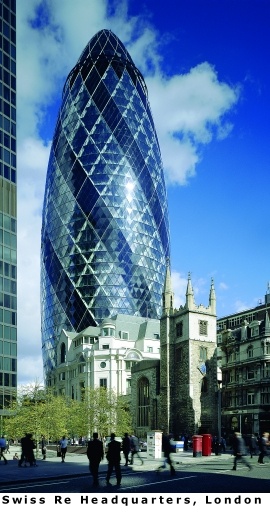

Best examples? The first post-war

icon was the little church at Ronchamp by Le Corbusier. This building

set the standard for all subsequent work in the genre. Other recent

ones I could mention include Daniel Libeskind (Imperial War Museum,

North Manchester; Jewish Museum, Berlin), Norman Foster (Swiss Re

headquarters, London), Frank Gehry (New Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao;

Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles).

When walking in an older (by

American standards) city like Philadelphia one feels a sense of warmth

and safety from the surrounding architecture. The buildings lining

the streets are constructed on a human scale and concerned with

how they fit in with their neighbors. Iconic buildings by contrast,

seem to care much less for the pedestrian and the surrounding architecture

and more for their impact on a skyline or an observer flying in

on a 747. Is this a valid criticism? Are the committees assigning

commissions for these buildings concerned with the pedestrian or

the city’s architectural fabric?

The

architectural fabric is the last thing the iconic architect considers,

if at all; which is why society should demand more of them. It is

not to say they can't do it, or there is an impossible contradiction

between iconic building and city. Rather they tend to be opposites,

and so need conscious reconciliation.

Do

you read anything into these buildings in terms of where we are

as a society? Could their narcissism be a sign of a culture in decline?

Do

you read anything into these buildings in terms of where we are

as a society? Could their narcissism be a sign of a culture in decline?

Narcissism? Culture in decline?

It's the whole world. Venice was narcissistic, full of iconic buildings, and

declined for 500 years, but was still the most pleasant city to

live in for much of this time. It's important to realize the nuanced

situation of today and see that opposite forces are producing the

iconic building (decline of religion, rise of consumerism) plus

a strange historical juncture of freedoms, creativity, the computer

(as well as a collapse among the young of any commitment to traditions).

Tom Wolfe once argued that

American capitalism had mistakenly chosen staid, bureaucratic socialist

architecture to build its corporate headquarters. Now we have governments,

particularly in Communist China, commissioning these exuberant,

avant-garde buildings. What’s going on here?

China, and its Global Cowboy

Capitalism, is becoming like old Shanghai, just reverting to its

normal bumptious place driven by motives not far from San Francisco

during the Gold Rush. The fact that it has to be justified by weak

communism and the ruling Junta is no stranger than American politics

at the moment.

Is it possible that what attracts

us to these buildings is they’re unlike anything seen before? That

once they begin to be duplicated, we’ll find that “new and different”

is all there was to many of them.

Yes. Being almost unlike anything

before is important; yes that may be all there is in the majority

of cases (which are a failure). But that's why I have been at pains

to show why the good ones are different. They have many meanings

(unlike the one-liner) that relate to their place, function and

history; their meanings also call on a hidden cosmic code of nature:

that is, they are creative in a deeper sense.

Modern man lacks a mythology

that incorporates our latest discoveries in science, but you make

an eloquent case for something called “cosmogenesis.” Would you

please tell us what that is and how it manifests itself in architecture?

"Cosmogenesis" has a 150 year history as a word. It

is picked up by Teilhard, de Chardin,

Thomas Berry and Harvard physicists. It has come

to mean the universe as a continuous, unfolding event (i.e. a genesis,

by a cosmic process lasting 13.7 billion years). This is the shift

in worldview that sees nature and culture as growing out of the

narrative of the universe. In a global culture of conflict this

narrative provides a possible direction and iconography that transcend

national and sectarian interests. Several architects are involved

at different levels.

"Cosmogenesis" has a 150 year history as a word. It

is picked up by Teilhard, de Chardin,

Thomas Berry and Harvard physicists. It has come

to mean the universe as a continuous, unfolding event (i.e. a genesis,

by a cosmic process lasting 13.7 billion years). This is the shift

in worldview that sees nature and culture as growing out of the

narrative of the universe. In a global culture of conflict this

narrative provides a possible direction and iconography that transcend

national and sectarian interests. Several architects are involved

at different levels.

One

can discern the beginnings of a shift in architecture that relates

to a deep transformation going on in the sciences and in time will

permeate all other areas of life. The

new sciences of complexity - fractals,

nonlinear dynamics, the new cosmology, self-organizing systems -

have brought about the change in perspective. We

have moved from a mechanistic view of the universe to one that is

self-organizing at all levels, from the atom to the galaxy. Illuminated

by the computer, this new worldview is paralleled by changes now

occurring in architecture.

The

plurality of styles is a keynote. This reflects an underlying concern

for the increasing pluralism of global cities. Growing out of post-modern

complexity of the sixties and seventies - Jane Jacobs and Robert

Venturi - is the complexity theory of the 1980s: Pluralism leads

to conflict, the inclusion of opposite tastes and composite goals,

a melting and boiling pot. Modernist purity and reduction could

not handle this reality very well.

The

Death of God, like the death of other major narratives over the

last hundred years, may be confined to the west, especially visible

now that the globe is experiencing the ultimate clash of civilizations.

But fundamentalisms, either American or Other, are not living cultural

movements however powerful they may be. They have produced no art,

architecture or writing worth preserving, and the deeper problems

remain. In spite of these problems, the question of whether the

new paradigm exists in architecture is worth asking. What we’re

seeing may be a false start; the old paradigm of Modernism can easily

reassert its hegemony, as it is lurking behind every Blair and Bush.

But a wind is stirring architecture; at least it is the beginning

of a shift in theory and practice.

Paul Comstock, October

16, 2005